By Dr. Shelley

•

January 5, 2021

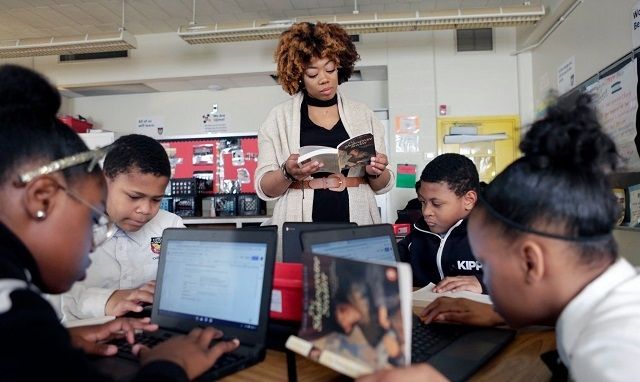

This February, I coached a fourth grade teacher in the Detroit Public School Community District. Inequities in state funding and white flight have helped make the school’s demographic 99% African American. This is the kind of institution educator and activist Jonathan Kozol labeled an “apartheid school” in his book, The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America. The district recently adopted the EL Education Curriculum which requires students to read grade level text and write essays. Student protocols, a major component of EL, are embedded in each lesson to promote discussion among the students. That day, students were going to share their writings with a peer. At the teacher’s direction, boys and girls eagerly moved to sit next to a partner. As I scanned the room, I noticed a young boy sitting next to a girl with his paper in front of them. This fourth grade boy looked defeated. He slumped in his seat while nervously looking at his paper. I walked over to the pair. “Jamal, may I help you?” As I glanced at his neatly written, three-paragraph paper, only the word “lion” was spelled correctly. He painstakingly wrote the essay as instructed but could not spell or read his own writing. For a nine-year-old student, this was devastating but Jamal was doing everything he could to succeed. If black children are going to motivate themselves and determine the direction of their own lives, basic literacy skills are not enough. They must also learn how to be self-respecting in a caring community of like-minded people that listens and encourages other’s ideas. When each of these elements is nurtured, students thrive. This places a tremendous responsibility on all educational stakeholders including state representatives, administrators, and teachers to create an environment that fosters students’ psychological as well as instructional needs. For hundreds of thousands of students, neither of these needs are being fulfilled simply because reading instruction has failed them. In 2016, seven Detroit students filed a suit against the State of Michigan documenting alarming conditions in rodent infested, crumbling schools that lacked certified teachers and up-to-date textbooks. The students argued that the state was responsible for those conditions since it controlled Detroit’s main school district for nearly two decades leading up to the suit. The students also said they were relegated to a school system that does not offer a plausible opportunity to attain literacy. Two years later, a trial court judge agreed that the conditions were deplorable but threw out their case because he said the Constitution does not guarantee the right to an education or literacy. Students fought the ruling and the trial court’s judgment was appealed. Two out of three circuit court judges ruled in favor of the students this April. The suit was settled in May with the seven students receiving payments and Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer designating almost $100 million to promote literacy initiatives in Detroit, including the creation of the Detroit Literacy Equity Task Force and the Detroit Educational Policy Committee. The settlement means the students agreed to drop their accusation that the state denied a basic education; however, there is still no Constitutional right to literacy, and future courts do not have to acknowledge this case. According to the 2019 National Assessment for Educational Progress (NAEP), there has been no significant growth in students’ reading comprehension and skills over the last 30 years. The reading assessment is given every two years to students at grades 4 and 8, and approximately every four years at grade 12. About 150,600 fourth-graders from 8,300 schools and 143,100 eighth-graders from about 6,950 schools across the nation participated in 2019. Scores are also disaggregated by race and ethnicity nationwide: - Asians scored 239, Whites 230, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander 212, Hispanic 209, and both Black and American Indians/Alaska Native scored the lowest at 204. The 2019 results also indicate the percentage of students scoring at or above proficiency. For the nation, 34% of students; in Michigan, 32%; and, in the City of Detroit, 7%. These figures indicate an alarming failure in teaching students to read. Over the past few years, I have organized several forums in Detroit and Houston on the literacy gap between African American and white students. If students fail to read proficiently, they not only face immediate danger of academic failure, but also the long term possibility of living in poverty. In a 2013 article in Educational Leadership, Dr. R. Martin Reardon noted that if the reading gap is not closed, today’s students will be unable to provide for themselves as adults. While the movement against police brutality in response to George Floyd’s death has been encouraging to watch, the struggle to ensure every Black child lives a dignified life is just as active in the field of education. In the late 1970s, debates about the best ways to teach children how to read usually happened between advocates of a phonics-based approach and those who supported the now discredited whole language philosophy. Whole language proponents believed that students learn to read naturally. Initially, whole language supporters won when the California and Texas Department of Education the largest purchasers of textbooks in the country adopted the philosophy. A domino effect rippled through every educational entity while increasing profit for publishers and professors. Teacher preparation programs graduated teachers whose reading instruction methods were flawed helping create generations of illiterate students over a span of three decades. ***** When I was in graduate school, I had to take a reading instruction class. The professor was an advocate for whole language. In fact, our textbook was a draft of her unpublished typewritten manuscript. She ensured the class there was no need for alarm since her book would be published very soon. In one class session, I told the teacher that I had experience teaching children to read before kindergarten. I served as the director of a faith-based children’s institute called Mtoto House, a program within a Black Christian Nationalist church in Detroit founded by the prominent civil rights leader Albert B. Cleage, Jr. Its purpose was to develop children socially, spiritually, physically, and academically. In the mid 1970s, I adopted the Direct Instruction approach to reading in our nursery program with children ranging from two to five years old. This approach continued as children matriculated from early childhood to upper elementary school. When students entered kindergarten, they were already proficient in reading. By the time they reached third grade, they were reading on an eleventh grade level. My professor asked, “What did you use?” I answered, DISTAR (Direct Instruction System for Teaching Arithmetic and Reading), a phonics based program that ensures the best outcomes for students. She immediately responded, “Oh, we don’t like that.” Besides the wealth of neuroscientific evidence from researchers like Stanilas Deheane which finds that reading doesn’t come naturally to students, there was another problem with whole language; it was harming the emotional well-being of students. Flawed reading instruction worsened students’ depression, made them withdraw, and prompted them to flaunt teachers’ authority. I applaud the students who filed the “right to literacy” lawsuit and those adults who fought by their sides. Their passion, consistency, and ultimate victory are commendable. But, if old methods of reading instruction aren’t changed, no amount of money will improve prospects for Detroit’s students. All stakeholders, administrators, and educators need to address literacy by intentionally creating an empathetic environment with explicit teaching methods that guarantee students will learn to read. Students’ futures, and ability to one day provide for their families are at stake. ***** Fifteen minutes of students exchanging writing samples were over. The teacher rang her bell signaling students to return to their assigned seats. I asked permission to work with Jamal one-on-one. She consented and went to help another group of students with their writing. I sat next to Jamal with his misspelled essay in front of us. I pointed to the first line. “Jamal, what were you trying to say here?” He responded, “The lion is a predator.” (Jamal learned this information through hearing in class discussions) I wrote his exact words on my sheet of paper. I then told him to write it exactly as I had on a clean sheet of his own paper. Placing my finger on each word, I modeled the pronunciation, sounded letters out, and blended sounds into words. Then, I asked him to repeat it with me. Lastly, I showed him how to do it by himself giving corrections when needed. For forty-five minutes we went through this arduous process for each sentence until he could write, spell, and read a full paragraph without error. Learning to read is hard! Jamal smiled. After students left for gym, I shared the process with the teacher. Her eyes filled with tears of sadness because she was fully aware of Jamal’s reading challenges and how hard he tried and with tears of happiness knowing that he did it. His need to succeed had been nurtured.